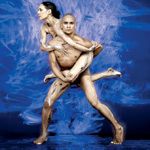

Bangarra, from the Wiradjuri “to make fire” still burns with creative energy after 20 years with an extensive touring schedule this year and a retrospective production, Fire, opening in August. It is a wonder that artistic director and choreographer Stephen Page has time to reflect on how it all came to be.

There’s a practical side to Stephen Page that recognises that 20 years is a long time for any Australian arts company, let alone one specialising in Indigenous dance.

Then there’s another part of him that reaches into his blackfella side and says: “Twenty years or 20,000 years, it’s nothing.”

Such has been the high-wire balancing act for Stephen, who has been the Artistic Director of Bangarra Dance Theatre for 17 of its past 20 years, juggling cultural protocols and responsibilities with the pressures of regional, national and international touring of one of Australia’s flagship arts companies.

Talking to him about the 20th anniversary of the company this year, there is a strong sense of a shared spirit, of the Bangarra family and those who were instrumental in its beginnings.

It’s inevitable though, as the person at the creative helm through most of Bangarra’s cultural ascendancy, that much of the attention will focus on him. The Stephen Page of today is more analytical and self aware than the brash youth whose creative energy drew others into his circle, propelling the company to prominence in the early ’90s.

“You accept your own creative ego and I know now how to measure it,” he says. “I know what’s productive and in the way you have to be really critical.”

Stephen’s background has been well-documented, a descendant from the Nunukul people and the Munaldjali clan of the Yugambeh tribe from southeast Queensland, he grew up in the tough Mt Gravatt area of Brisbane, the second youngest of 12 children. Play performance in the backyard, with Stephen directing, was a natural part of growing up for the Page family.

The pathway that led to the establishment of Bangarra in 1989 is a convoluted one, intertwined with the Black Theatre in Redfern and the development of the National Aboriginal and Islander Skills Development Association (NAISDA), the college for young Indigenous dancers where Stephen trained.

Certainly though Carole Johnson, a black American dancer who came to Australia with the Eleo Pomare Dance Company and stayed, was an energising force in the development of contemporary Indigenous dance and a founder of Bangarra, with the name of the company drawn from the Wiradjuri word “to make fire”.

By the time Stephen was appointed artistic director in 1991, he had already danced with Sydney Dance Company and had several choreography credits to his name.

“I had no fear then,” he says. “You’re young and I just dived into deep water.

“It was the best of the creativity, we were all into telling stories. I don’t think we really analysed, we were in the moment.”

Instrumental, literally, in those early days, was the creative relationship formed between Stephen and Djakapurra Munyarryun from Dhalinybuy in north-east Arnhem Land.

Stephen had directed an end-of-year production for NAISDA in 1989 and Djakapurra’s sister Janet was a cultural consultant. When one of the yidaki (didg) players was missing one day, Djakapurra, who was in Sydney visiting his sister, jumped in.

“He was promised to sing, dance and play the yidaki, which is very rare,” Stephen says. “He just fell in love with the whole idea of telling these contemporary stories using the old and the new. So he just hung around us. He was only supposed to be down for two weeks but stayed for 10 years.”

Stephen also gathered around him his brothers Russell and David. With David creating an original contemporary music score and Russell dancing the lead, Praying Mantis Dreaming, Bangarra’s first full-length production made its debut in 1992.

For the first time, here was a contemporary Australian Indigenous dance company celebrating and acknowledging its cultural identity and heritage in an urban setting.

“That breaks my heart because it means there was a lost generation,” Stephen says.

A new strong, feminine energy emerged when Frances Rings joined the company in 1993.

“They (David, Russell, Djakapurra and Frances) were the muses of the repertoire, they brought the uniqueness to the company,” Stephen says.

“It caused some good damage in the industry. Bangarra became a leader in the arts and with that came responsibility.

“As cultural ambassadors we carry the Aboriginal flag. Fortunately, the traditional clan groups have trusted the company to carry that cultural knowledge out into the broader community.”

Stephen also considers it fortunate to have had the solid financial footing of Bangarra and a company of up to 12 dancers with which to create productions that have astonished audiences from remote outback communities to international stages. About 90 dancers, most of whom are familiar names now to Indigenous audiences, have passed through Bangarra in that time.

“Having all that energy in the same environment is very healthy,” he says.

Even into the 21st century with a new generation of dancers emerging, Stephen remains restless.

“Art and storytelling as medicine is such a huge part of our lives and it shouldn’t be struggling,” he says and yet, outside of Bangarra, he recognises that much of the Indigenous performing arts struggles. He’d like to see more recognition of the cultural workshops component of Bangarra’s annual schedule, which is as important as the performances, as well as more international Indigenous dance exchanges.

For the 20th anniversary, Bangarra will present the retrospective Fire, “a once-only chance to experience a kaleidoscope of works that have brought the company to the attention of the world”.

“It will be the first time that we’ve used audiovisual and multimedia components. I’ve just really felt the need to do it before,” Stephen says. “I’m trying to do the representative serpent production that looks at the past 20 years.”

Bangarra’s remaining touring schedule for this year is:

Comments are closed.