Trachoma is a preventable condition that is almost entirely a disease of undeveloped countries. However, while mainstream Australians rarely – if ever – contract trachoma, the condition is rife in many Indigenous communities.

What is trachoma?

Trachoma is a contagious infection of the eye caused by bacteria. It’s the leading cause of blindness worldwide, affecting over 400 million people. It’s one of the earliest-recorded eye diseases – with records of it dating back to the ancient Egyptians.

Trachoma is caused by a bacterium called Chlamydia trachomatis, which affects the eye and causes scarring, in-turned eyelashes and blindness if left untreated. It’s spread from person to person by affected people – usually by young children who pass on the disease by touching their eyes and then other children. Flies can also transmit it.

Trachoma is only ever seen in areas where living conditions are crowded and hygiene is poor, and is known to be endemic in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations in some parts of the Northern Territory, South Australia and Western Australia.

What are the symptoms?

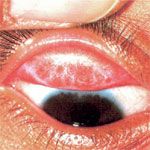

Trachoma causes inflammation of the cornea (the clear centre part of the eye) and the conjunctiva (the transparent layer of tissue that covers the white of the eye and lines the inside of the eyelid).

Initial symptoms include a stinging in the eye, light sensitivity and swelling of the eyelids. If this is left untreated, the conjunctiva thickens and starts to scar. This scarring can make the eyelid turn in, and the rubbing of the eyelashes on the inside of the eye causes ulcers. The tear glands also develop scarring.

Repeated infections without treatment can make the scarring so bad that it causes blindness.

How is it treated?

Trachoma can be treated quickly and easily with antibiotics. If the condition has been left untreated for so long that the eyelids have turned in, simple surgery is required.

Keeping the face and hands clean with frequent washing can stop the infection from spreading to others.

What is being done?

Over 30 years ago, a national program was launched to eliminate the disease. But today, trachoma is still widespread in outback Indigenous communities, especially in the Northern Territory and Western Australia.

A recent survey, conducted by Professor Hugh Taylor, a leading ophthalmologist (a doctor who specialises in eye diseases) from the University of Melbourne’s Centre for Eye Research Australia, shows that effectively no progress has been made in eradicating trachoma in Indigenous communities.

Professor Taylor found that up to half of all children in some communities have trachoma and that one in 12 adults have in-turned eyelashes from having trachoma as a child.

Infection was more common in inland and remote areas, while coastal communities were not so badly affected because children’s faces were kept cleaner by swimming and playing in the water.

This year, Professor Taylor’s research centre will start work on a National Indigenous Eye Health Survey. He hopes that the survey will encourage the Federal Government to fund a national trachoma prevention program.

If you or your child experiences any kind of eye problem, make sure you see your GP or visit your Aboriginal Medical Service immediately.

Comments are closed.