Deadly Vibe Issue 111 May 2006

Deadly Vibe Issue 111 May 2006

Most film sets are unlikely to need crocodile spotters. And most films are unlikely to feature an entire cast that has never acted before. But for Rolf de Heer’s new film Ten Canoes, these were just two of the many unusual circumstances that have made this film one of the most unique and exciting ever to hit our screens.

Ten Canoes is a comedy/drama set in the remote Arafura Swamp over a thousand years ago, and is the brainchild of both Rolf and Aboriginal actor David Gulpilil, who had previously worked together on The Tracker.

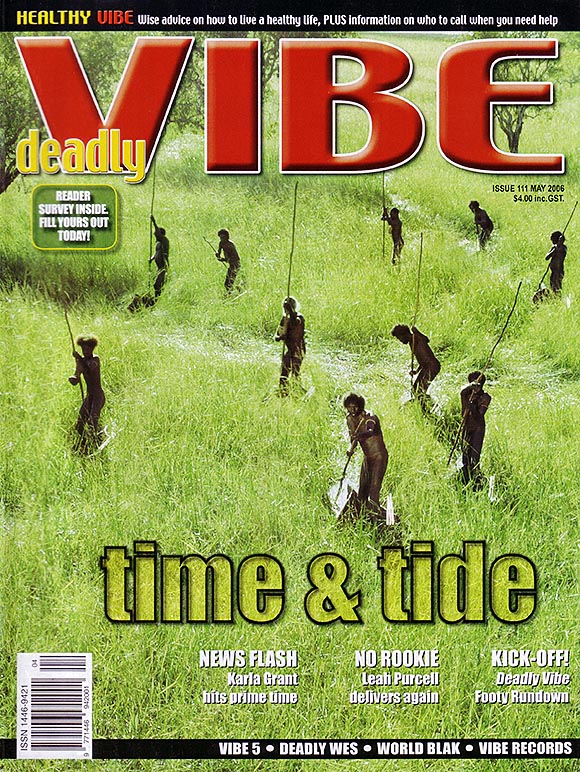

Spoken entirely in traditional Ganalbingu language, the first feature film in an Australian Indigenous language, Ten Canoes begins with 10 men, led by tribal Elder Minygululu (played by Peter Minygululu) heading out to harvest bark for canoe making. It’s the season of goose egg gathering, and the men are looking forward to getting out onto the swamp and hunting for eggs.

On their first hunting expedition, Minygululu learns that young Dayindi (played by David’s son, Jamie Gulpilil) has taken a fancy to one of his wives. To teach him the proper way and to ensure that tribal law is not broken, Dayindi is told a story from the mythical past. This story forms the basis of Ten Canoes.

Narrated in English by David and shot in both black and white and colour, this subtitled film is a fascinating look at an ancient culture, a celebration of a proud people, and an opportunity for the world to learn about the oldest race in the world.

The idea for the film came from a photograph taken more than 70 years ago, of a group of 10 men in their bark canoes on the swamp. For David and Rolf, this image was profoundly cinematic. It spoke of a world of long ago, where things were different, and life was different to anything that could be imagined by almost any Balanda (whitefella) anywhere.

“I showed a photograph to Rolf and said what do you think?” David says. “He started to write that story with Ramingining people, my people, and we started to work together.”

The photograph was taken by a man named Donald Thompson, an anthropologist (a scientist who studies human beings) who worked in Arnhem Land in the 1930s. The thousands of photographs that he took give an amazingly in-depth view of a people in a slice of time that may otherwise have been forgotten, and gave the filmmakers the precise details they needed to correctly represent the Yolngu culture.

“What the community wanted was some sort of preserved culture record,” says Rolf, whose other films include Bad Boy Bubby and Alexandra’s Project. “They wanted a movie that would be seen by the world; because it is very important for them to show their culture and have it understood that their culture has value.”

The community were involved in the entire process, from the development of the script through to post-production.

“Every time we’d watch rushes (the results of the day’s filming), they’d scream with delight and just be loving it and be moved and be crying,” Rolf says.

To give the production true authenticity, all the artefacts needed for the film were made by the Yolngu, the canoes, the spears and stone axes, the dilly bags and shelters. The entire cast of the film was made up of people indigenous to the Arafura Swamp area, Ganalbingu and related clans from the nearby Aboriginal community of Ramingining, all of whom had never acted before.

Eleven croc spotters were hired to protect the crew, who were often waist-deep in the swamp for hours at a time. For Rolf, it was the most physically challenging film he has made.

“When you’re in the swamp up to your waist with the leeches getting you from the waist down, the mozzies from the waist up and the blokes are in the trees saying, “There’s a big one coming and they mean a crocodile, it’s not very comfortable,” he laughs.

For the cast, making the film was a chance to reconnect with a past that they had begun to lose touch with.

“When I’m acting out in the swamp in the canoes, I feel full of life,” says Bobby Bunungurr, who plays a Ganalbingu songman in the film. “The spirits are around me, the old people they with me, and I feel it. The spirit of my older people they’re beside me and they’re giving me more knowledge.

“That’s why we worked and no-one was bitten by a crocodile, because the spirit of the older people were with us.”

Ten Canoes had its international premiere at the Adelaide Festival of the Arts in March, with 18 members of the cast and crew travelling from Arnhem Land to attend.

“When they showed me the film and the film started, I start to cry,” David says. “I remember those days, I remember . . . and now I can see it in the film. I saw it.

“I really want to thank Rolf, what he done for my people and my people’s story and a true Australian story, fair dinkum.”

Storytelling is a central part of Yolngu culture, and although its conventions differ to those of Western storytelling, the fascinating nature of the story of Ten Canoes, the compelling characters and the accuracy of the portrayal of Yolngu culture all serve to make this intriguing film something to bewitch audiences from all walks of life.

“That story is never finished, that Ten Canoes story,” David says. “It goes on forever because it is a true story of our people, it is the heart of the land and people and nature.”

Deadly Vibe Issue 111 May 2006

Deadly Vibe Issue 111 May 2006

Comments are closed.