Aboriginal jockeys and the ‘Sport of Kings’

Based at the University of Newcastle’s Wollotuka Institute, Professor John Maynard is one of the country’s foremost historians. His books have covered Aboriginal soccer, and the Aboriginal rights movement, and he is currently working on a major research project – Serving Our Country – about the Aboriginal people who served with the Australian Armed Forces.

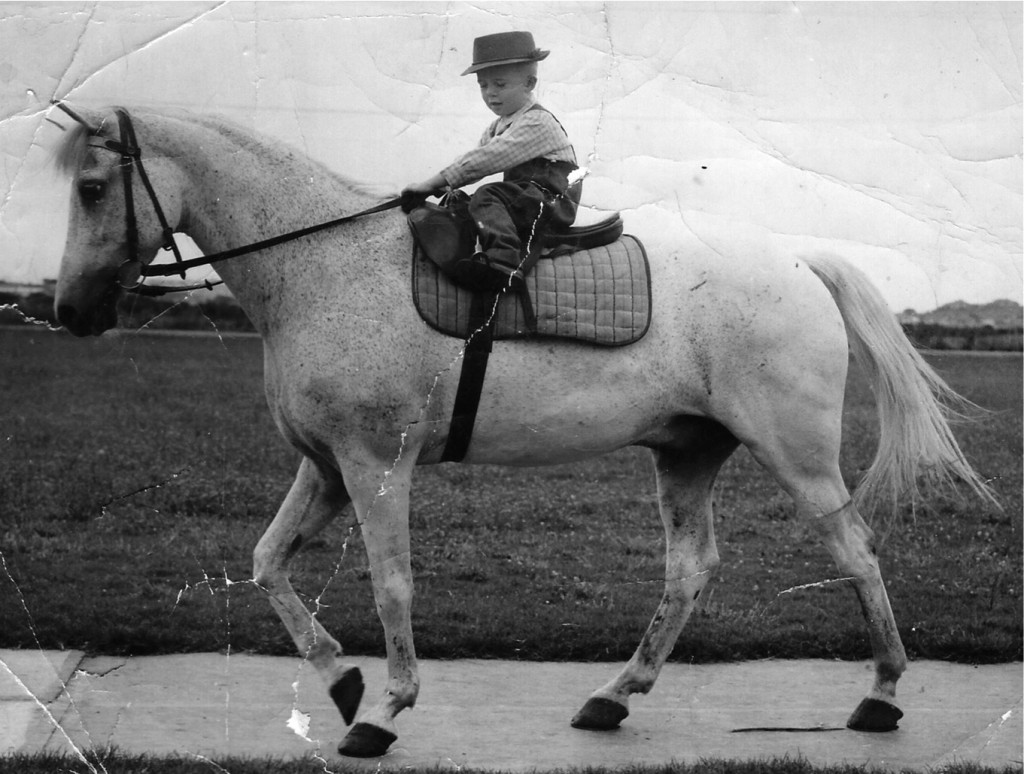

From Worimi country around Port Stephens, north of Newcastle, Maynard started out writing about his family, including his grandfather Fred, who as President of the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA) was an early leader in the fight for self-determination during the 1920s and 1930s. The inspiration for his book Aborigines and the ‘Sport of Kings’ is his father, Merv, who won more than 1500 races as a jockey in Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and Malaysia.

Merv features in the book, which is his son’s attempt to fill in a part of Australian history that has largely been ignored. “Horseracing is a significant part of Australian culture. As the largest racing country in the world, Australia has 66 of the world’s 193 Group One races and more racecourses than any other nation. However, despite this, we know very little about the contribution Aboriginal people have made to the sport,” Maynard said.

The book provides an account of the careers of a number of famous Aboriginal jockeys and the barriers they faced from racist attitudes that persisted despite clear evidence of their ability.

“During the 19th century, Aboriginal jockeys were frequently banned from the track. Others won big races, but their names were simply recorded as Sandy, Jacky or Darky,” Maynard said.Some jockeys had to deny their Aboriginality in order to be able to compete. A likely example is the jockey Peter St Albans who won the 1876 Melbourne Cup before a fall in Sydney enforced his early retirement. Although the evidence is mixed, and some writers have argued against his Aboriginality, for Maynard, St Albans’ background “remains a mystery still to be solved. And where there’s smoke there’s fire,” he said.

Some of the great stories in the book involve jockeys who escaped harsh treatment at the hands of the Australian stewards to find fame and fortune overseas. One was Rae “Togo” Johnstone. After a series of heavy suspensions he left Australia in 1931 and ended up racing in France where he married a chorus girl from the famous Folies Bergere, then he was hauled off to a Nazi prison camp during World War Two, from where he escaped to join up with the French Resistance. After the war he enjoyed an amazing career. In 1948, he became the first jockey to win the English, French and Irish Derbys in the same year, a feat that has never been repeated. During the early 1950s he was probably the highest paid sportsman in the whole of Europe.

Another to star on European tracks was Darby McCarthy, the son of a Cunnamulla stockman. Proudly Aboriginal, he accepted a lucrative offer from French trainer Maurice Zilber. It was a far cry from his origins.

“At Cunnamulla, we lived between the cemetery and the sewerage outlet, mate. Blacks weren’t allowed up in the town mind you. What’s even more important, I couldn’t vote in my own country, brother,” says McCarthy in the book. In France, though, he ended up with a fat salary, a car and a two-storey house in Chantilly complete with a French maid. He went partying with the likes of Frank Sinatra, Mia Farrow, Lee Marvin and Rock Hudson.

McCarthy was able to take advantage of the social movement of the 1960s, where events like Charlie Perkins’ Freedom Rides helped Aboriginal people get the same rights as other Australians.

Other stars of that era that the book mentions include Frank Reys, who won the Melbourne Cup in 1973. Women also benefited from social change, and in the 1970s they were finally allowed to race as jockeys. In 1998, Leigh-Anne Goodwin became the first Aboriginal woman to win a metropolitan race when she brought Getelion home first at Brisbane’s Eagle Farm. Tragically, she fell badly at Roma in Queensland three months later and died. Maynard has dedicated the book to her.

In recent years, the number of Aboriginal jockeys has fallen off. Maynard attributes this partly to the increasing popularity of football, rugby league and Australian Rules in Aboriginal communities. Another reason he gives is the movement of Aboriginal people from the country to the cities in search of work.

For Maynard, growing up around the racetrack was exciting, but it soon became apparent that he would grow too tall to be a jockey. “I was about 12 or 13 and we were sitting around the breakfast table one morning when he (Merv) said ‘Son, if you’ve got any desire of being a jockey, my best advice for you is to go to India and ride elephants.”

Comments are closed.