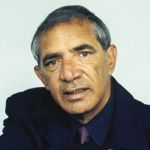

This year’s 7th Deadly Sounds Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Music Awards (aka ‘the Deadlys’) saw a swag of music legends converge on cityLIVE, Fox Studios for a night of grassroots musicianship with a country twist. Some sang. Some collected awards. And some, like William Victor Simms, did both.

Taking to the stage like the consummate professional that he is, trademark tambourine in hand, Vic demonstrated that age need not weary those who know the grooves and still have the moves. With able backing from Michael Donovan’s house band, the man who once shared the bill with the likes of Col Joye, Johnny O’Keefe and Shirley Bassey let rip with a sizzling set that reminded anyone who’d forgotten that this singing dynamo was – and still is – ‘the real thing’.

Later on, he was called back to the stage for a very special reason. In a break with tradition, two people were honoured with a Deadly for Outstanding Contribution to Aboriginal Music. One was the grandfather of Aboriginal music in the Northern Territory, Gus Williams. The other was Vic Simms.

“Receiving that Deadly has been the highlight of my career,” says Vic with simple conviction a week after the awards. “And to be able to share it with Gus Williams is nothing short of an honour and a privilege. Without Gus’ fortitude and encouragement over the years, we wouldn’t have Frank Yamma or Coloured Stone or Bart Willoughby.”

Such modesty belies the fact that, were it not for Vic’s example over the years, Aboriginal music wouldn’t be the thriving and diverse industry that it now is. Back when he started, as a shy 12 year old singing with Col Joye’s troupe of musicians at the Manly Jazzorama Music Festival in 1957, Vic’s only Aboriginal contemporary was Jimmy Little, who had moved to the big smoke from Nowra two years earlier.

Vic remembers meeting Col and his brother Kevin the year before at a football social in Maroubra Junction.

“It was at this little hall out the back of a milk bar and they had a group there called the Kevin Jacobsen Quintet,” he says. “They were playing a mixture of country, MoR and rock ‘n’ roll. After about two hours they took a break, but not before daring someone from the audience to get up and sing. All my mates immediately started pointing at me going, ‘He can sing! He can sing!’ So I got up and did a couple of songs – ‘Red Sails in the Sunset’ and ‘Tutti Frutti’. They asked me to sing some more, but I couldn’t because that was my entire repertoire at that stage!”

Regardless, Vic’s extraordinary musical talent had been clocked by a pair of brothers who would go on to be key founders of popular music in Australia. In the months following, he didn’t really know what to think of his little turn in the spotlight. That is until the Jacobsens turned up at Vic’s La Perouse home with a proposition for his mum.

“They wanted me to do the Jazzorama job with them in Manly. Johnny O’Keefe would be there too. I couldn’t afford any fancy clothes or anything, but they bought me a pair of jeans and a shirt, shoes and socks. We played five nights at the Manly Embassy and I earned a total of 36 shillings.”

One vivid memory Vic has of that week concerns a rather faddishly dressed JO’K exhorting him not to wear jeans. “He said ‘You’ve gotta dress suave, kid. Jeans are out daddy, no cat wears jeans.’ He had a way with words.” After the festival, Vic successfully auditioned for a ‘fill-in’ skit at the legendary Tivoli as part of Shirley Bassey’s first Australian tour.

Quite simply, Jazzorama was the beginning of a career that is still going to this day. When Col & the Joy Boys’ “Oh Yeah, Uh-Huh” and “Bye Bye Baby” became smash hits, Vic was invited to hit the road with this eclectic collective of clean-cut musos. They played at dances, police boys clubs, on the club circuit and appeared regularly on such television programs as Bandstand, The Johnny O’Keefe Show and the various In Melbourne/Adelaide/Brisbane Tonight shows.

Vic released his first single, “Yo-Yo Heart” at age 15 on Festival Records. “I’m Counting Up My Love” followed a year later. Although he still lived in a rusty tin shack in La Perouse, his growing success enabled him to buy some nice clothes and put a bit of money away. He remembers being paid what he felt was “exorbitant money at the time” to do commercials for Dairy Farmers.

During these formative years Vic travelled widely throughout Australia, experiencing things his family and friends back home could only dream about. But the endless touring did have its disadvantages.

“In the industry itself I experienced no prejudice and was totally accepted by my peers for my musical ability. I was simply ‘Vic Simms, Entertainer’. But in some towns, while it was okay for me to be onstage, as soon as I walked off no one wanted to know me. One night I was set upon by a group of bikies in Tamworth when I was 15 or so. They called me a black bastard and accused me of big-noting myself before laying into me.”

Another time Vic and the Col Joye entourage, including a young Peter Allen, were frolicking around in Moree’s swimming pool enjoying the sunshine, when Vic was coldly informed he would have to leave. “The attendant said to me, ‘It doesn’t matter if you’re here with the Prime Minister, you’ve got to leave. We don’t let people like you in here.’ I said, ‘What do you mean?’ and he replied, ‘Black people, Aboriginal people – have a look around.'”

When Col and the rest of them saw what was going on, they all collected their things and left in a show of solidarity. “They said, ‘If he’s not good enough, then we’re not going to swim here either. You can stick it where the sun don’t shine.’ But I was gutted. I’d never experienced prejudice before. It affected me psychologically for a long, long time.”

For whatever reason, the good times didn’t last. When the Beatles arrived in Australia, they sent shock waves through the industry, effectively rendering anybody vaguely country, hillbilly or rock ‘n’ roll ‘old hat’. In addition, Vic was copping it from his mates back on the mission who were envious of his new-found lifestyle and relative freedom.

“They said I was getting too big-headed, that I had to come back to the fold. So I did. I started drinking while still at a very young age. We were all getting on cheap wine and getting into strife. I was trying to impress non-Aboriginal people on one hand and let my own people know that I was the same old me on the other.”

Full of internal conflict, Vic continued to tour and record, but he was fast losing the battle against alcohol and other bad influences. Eventually the dissonance between his performing life and his real life became too much to bear. And in 1968, Vic went to jail. He was 22. “I thought, this is it – everything’s gone now.”

One might expect Vic to have completely disintegrated in jail, to have wasted away to a shadow of his former self. Goodness knows the conditions were ripe for such ruin. Prior to the infamous Bathurst Jail riots in 1974, which blew the lid on the 19th-century conditions most prisoners endured, the NSW prison system had little respect for those within its care – and even less for blackfullas.

But the shadows of the prison bars that fell across his cell only inspired Vic to new heights of self-analysis and musical creativity. As he himself says, “Once a performer, always a performer”, and before too long the former child star from La Perouse was making some “Jailhouse Rock” of his very own.

“I had a reputation, so I was able to brings groups of able musicians together in prison,” he says. “We started doing some concerts. Then they allowed guitars into the prison and I bought one for two packets of Drum tobacco. I’d been writing some verses down about the things I saw around me, and so I began fiddling about with melodies. People showed me where to put my fingers on the fretboard and before too long I had 10 songs, each with a completely different melody.”

Representatives from a social cause group called the Robin Hood Foundation heard Vic singing in the yard one day and asked him if he would be willing to put his tunes on a cassette. Vic obliged and even ‘rehearsed’ his repertoire for his cell neighbours thanks to Bathurst Prison’s acoustically sensitive sewerage system.

“I sat right next to the toilet bowl with my guitar and played these songs to the guys in the cells around me, to get their opinion. They thought they were good, so I sent the tape away.”

The Robin Hood Foundation subsequently passed the tape on to RCA Records, whose A&R manager Rocky Thomas was so bowled over that he contacted the Department of Corrective Services with a novel idea. With the prison system in disarray, the idea – for RCA to record Vic live in jail and release it as an album – was greeted as a PR version of the proverbial manna from heaven.

After some toing and froing between Sydney and Bathurst, a mobile studio was eventually dispatched to Bathurst Jail’s dining hall where The Loner was recorded in a single one-hour take in June 1973. Session musicians were supplied for the day and Rocky produced the album.

Vic remembers: “We had an exact hour to record, because that was all the time allotted by the prison. The screws didn’t like it at all. They thought it was all about pampering prisoners – and a blackfulla at that! It was the end of the world for them. I had to hope and pray that I’d do okay on each of the 10 tracks because there’d be no second bidding. And I did.”

In an attempt to counteract the growing criticism they were attracting, Corrective Services decided to send ‘model prisoner’ Vic Simms out on the road. He toured other prisons, sang in shopping malls and appeared at the Sydney Opera House four times. Meanwhile, Bathurst Jail’s inmates were rioting after years of mistreatment. Eventually the Nagle Royal Commission made public the conditions that prisoners like Vic had endured for years: freezing cells without glass in the windows; beds regularly wet from rain and sleet; frozen water pipes; overflowing toilets.

“I felt that if I didn’t record that album, it would just prove that we were out of sight and out of mind,” he says. “I wanted to show that musical talent could exist no matter where it was, out in the bush or behind walls.”

That said, Vic admits he didn’t know what he was getting himself into when he agreed to tour.

“I didn’t realise I was being exploited in an effort to take the bad light off the prison system. A lot of prisoners I’d known for years became resentful. One of them said to me, ‘You’re just a show pony for Corrective Services. They’re putting you up front to make it seem as though everything is rosy.’ So I bucked. I said I wouldn’t do it anymore, count me out. I didn’t want a knife in my ribcage, and I was the one who had to go back to Bathurst Jail when it was all over. I had to live by the rules that existed there.”

Punished for refusing to finish the commissioner’s PR exercise, Vic found himself transferred to Parramatta Jail in handcuffs – restraints that had never been used during his many ‘outside’ appearances. “I was punished for jacking up, placed in the isolated sector. They said they’d put me in this place where nobody would ever see me again. I said, ‘Fine by me.’ Finally they let me out when they realised they couldn’t break me.”

Following his release in 1977, Vic set about mending his life. He began by entering talent quests in an effort to get his confidence back. He soon graduated to performing at Aboriginal country music festivals, recording tracks for the Koori Classics compilations, and even returning to the club circuit for the Johnny O’Keefe Memorial Show.

Then Vic did an amazing thing. While most who’ve spent time inside would baulk at the idea of ever returning there, the lad from La Perouse got a little group together – Roger Knox, Bobby McLeod, Col Hardy, Mac Silver and sometimes Jimmy Little – to go back inside and sing for the boys. Over a period of 12 years this collective of musicians travelled from jail to jail, letting the fullas – black and white – know that someone was thinking about them. In the process they opened the doors for the music industry to go into prisons.

This venture in turn led to a visit to Canada with Bobby and Roger in 1990, where the trio performed in numerous federal and state prisons. “The majority of prisoners in Canada are Native American people,” says Vic. “It’s very mirror image, right down to the reservations with their old cars and stray dogs. They’ve even got damper, except they call it bannock.”

Vic Simms has consolidated his position as a statesman and Elder for Aboriginal people in general and the La Perouse people in particular (his own mob is Bidjigal). Regularly called upon to officiate at numerous high-profile events as an envoy of Indigenous Australia, he is a wise and thoughtful man with a softly commanding manner and a natural storytelling ability.

Forty-five years is a long time in any industry, let alone the music business. Yet Vic shows no signs of slowing down and heading for Mercy Hills Retirement Complex in a Zimmer frame. A regular at Sydney’s Survival Day concerts, he’s currently compiling an anthology of 40 years of music, is hoping to get The Loner digitally remastered, and has recently begun work with a swing/jazz outfit.

“I’m 56 now and I don’t know how long I’ve got, but I want new challenges,” he says with a vitality that would do someone half his age proud. “I’m glad I’ve had the opportunity to do what I’ve done in my lifetime – but there’s a lot more to come, believe me!”

When Vic was presented with his Outstanding Contribution award last month, he was clearly moved at the extent to which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australia recognises and respects him as a living musical legend.

“It made me feel so good to get those accolades on the night and to be recognised after 45 years, particularly by the young guns. I’ve got wonderful support from my family too – my wife, children, nieces, nephews and grandkids. I’ve got a lot to be thankful for.”

Comments are closed.